Imagine that antibiotics were a new-ish thing in 2023. It’s likely that doctors would feel the same way about antibiotics today as they did in the 1940s, not just because antibiotics save lives and prevent suffering, but also because they prevent serious long-term consequences of untreated bacterial infections, such as rheumatic heart disease.

But would the public laud them as miracle drugs today as they did in the 1940s?

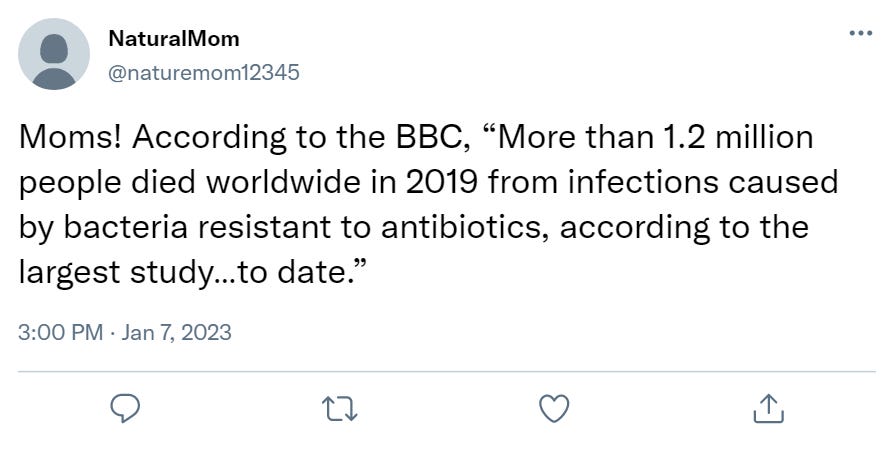

Some people would. But it’s easy to imagine a large segment of the public skeptical of antibiotics in 2023. Imagine the social media voices devoted to telling regular people, non-experts, about the dangers of using antibiotics. If you want clicks, engagement, or online fame, one way to get it is to frighten people. Fear sells. Danger sells. Imagine regular people reading these facts on Twitter1 about antibiotics:

All these are true facts. (They’re fake tweets from fake accounts, which I created for purposes of the thought experiment, but true facts.)

Imagine parents’ perception of the risks of antobiotics to their children’s health if they read about these dangers daily in their social media feeds, with sources like the CDC, BBC, other parents, and doctors. Many people would read these completely true statements — especially if they were barraged with them day after day — especially if the mainstream dismissed them as dummies or cranks or conspiracy theorists for believing true facts — and hesitate to give their kids these dangerous-sounding drugs. (“Conspiracy theorists? Dummies? It’s the CDC’s own data! You’re the dummy for mindlessly giving your kids these drugs!”)

Loss Aversion Kicks In

You might be familiar with the psychological principle of loss aversion, “the tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains,” first identified in the 1970s and replicated countless times since then.

It’s why your unhappiness at a $10 surcharge on your “free shipping” order is of a greater magnitude than your happiness at a $10 discount on an order with $20 shipping.

Because losses tend to be weighted more heavily than gains, people want to avoid actions that cause potential losses, even if it means giving up a potential gain.

Even monkeys seem to experience loss aversion, which might hint at how hard-wired this tendency might be in humans. In one experiment, capuchin monkeys preferred to get apple slices from someone who offered one apple slice consistently, as opposed to a person who initially offered two slices and took one away at the last minute. Either way, the monkeys got one apple slice from either person, every time. But they preferred the situation where they didn’t stand to “lose” anything.

Loss aversion might explain why parents are hesitant to “do something,” taking a very small risk that something bad could happen as a result, when “doing nothing” means status quo and their child will probably be OK. The pain of choosing a tiny but known potential loss (a bad outcome from antibiotics) is bigger than the happiness of a somewhat larger potential gain (antibiotics shortening the illness and possibly preventing death or disability), especially when the losses and gains are small, hypothetical, and abstract. It’s a fact that most kids are fine after bacterial illnesses.

Like the capuchin monkeys, parents don’t want to choose something where they might experience a “loss.” If you gave your kid penicillin and his skin fell off and he died, how would you feel?

In today’s social media environment, if antibiotics were new and parents were barraged daily with the scariest, most negative version of (true) information about the risks, you can imagine that many would develop a strong loss-aversion and it would be easy to justify withholding antibiotics:

“Most kids get a bacterial infection and they’re fine, right? Most kids don’t die from an ear infection or bronchitis. Most kids don’t go deaf or blind or develop scarlet fever or rheumatic heart disease from untreated infections. It’s surely best to leave well enough alone…isn’t it? If I give him antibiotics, his skin could fall off. He could die of Clostridium difficile. These are true risks.”

Even Irrelevant Information Can Be True

As if parents weren’t already scared enough in this scenario by the actual — if magnified — risks of anibiotics, imagine, if antibiotics were new-ish, that there were a database where everyone who received an antibiotic were encouraged to report any bad health incident that occurred after receiving it.

Now, think this through for a minute. This imaginary database is not for “established bad outcomes of antibiotics.” The database is for “every bad thing that occurred to anyone at any time after receiving an antibiotic.” The goal of such a database is to cast the widest possible net, to catch every possible bit of information, to see if there’s any signal, any signal at all, among the noise.

For example — moving away from our antibiotic example for a moment — within three months of the J&J covid vaccine being released on the market, Federal officials noticed a signal that there were blood clot cases among people who took this vaccine, at higher rates than among people who didn’t take the vaccine:

“Federal scientists identified 60 cases, including nine that were fatal, as of mid-March. That amounts to one blood clot case per 3.23 million J&J shots administered” according to the FDA.

You have to cast a very wide net to detect one case in 3.23 million shots . That’s the sort of signal that will never be detected in a clinical trial. No clinical trial in the history of clinical trials has ever been that big to detect a one-in-3.23-million risk. After clinical trials establish basic safety, researchers find out about smaller effects after drugs or treatments come to market, and the way you find out is by casting that wide net and looking at everything.

That signal, which was quickly identified, led to the vaccine disappearing from the market. Fortunately, there were no mustache-twirling villains at FDA or in the government trying to force a harmful vaccine on people once they identified a one-in-3.23-million problem with it. That’s the system working as it should.

But to detect those signals, scientists need to gather every bit of information they can, which includes a lot of noise. If you waved a toy magic wand over 3.23 million random people’s heads, and gathered every negative health outcome that happened to them after that, you’d see the whole gamut of bad health outcomes in that database: you’d find people who had cancer, pancreatitis, strokes, heart attacks, epilepsy, gonorrhea, AIDS, gout, migraines, appendicitis, kidney failure — and yes, people who died.

None of it, presumably, was caused by the waving of the toy magic wand.

Most of these databases are noise.

But, getting back to antibiotics: Imagine those database events being reported on Twitter now, too. It would be perfectly true to report that X number of people died, according to the database, after receiving an antibiotic. (It would also be true that a certain number of people died after we waved the toy magic wand over their heads.)

But what does that mean to the average parent reading it? “OMG X number of people died after receiving antibiotics!” means, to the average person, that the antibiotics had something to do with it. The average person doesn’t know what the databases are for. The average person doesn’t know how the data are collected, or why, or how they’re analyzed. It’s not their job to know.

It can be true that X number of people died, and also be completely irrelevant to making a good decision.

And Other True Facts

Imagine other true facts being thrown at parents:

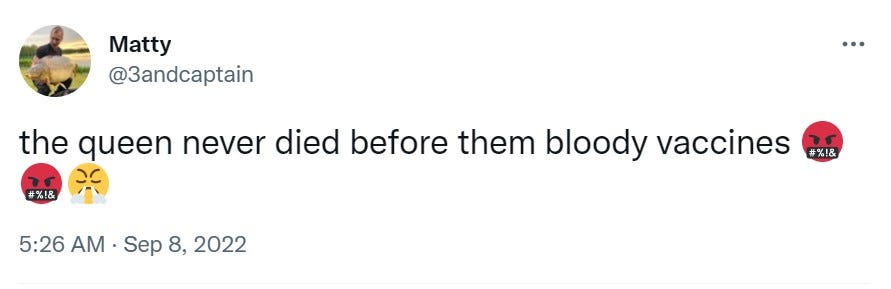

Imagine that every time a young person or a high-profile person died unexpectedly or had a health crisis, there were a chorus of people claiming that the person had taken antibiotics in the past. (Considering most people have had antibiotics at this point, that might be a true statement more often than not.)

My favorite example is this:

This is obviously a joke — but it’s a good example of true information that is also misleading. The Queen never did die before “them bloody vaccines.”

The other, more unfortunate example is the number of previously healthy young adults apparently dying unexpectedly of cardiocascular events.

Do you know what we know, for sure, causes previously healthy people to die unexpectedly of cardiovascular events? A history of covid infection — even a mild one, even a year ago. Covid messes up your blood vessels. It can cause clotting, sudden heart attacks, strokes, and pulmonary embolisms — if you “had a cold” a year ago, you could be forgiven for not connecting the dots.

But to lay the blame at the feet of the vaccine (for which no evidence exists of it causing messed up blood vessels, clotting, heart attacks, strokes, or pulmonary embolisms), when most people have had an infection known to cause those things — well, it’s a little odd.

(And if we’re going to have the myocarditis discussion: this systematic review and meta-analysis from August 2022 “found that the risk of myocarditis is more than seven fold higher in persons who were infected with the SARS-CoV-2 than in those who received the vaccine. These findings support the continued use of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines among all eligible persons per CDC and WHO recommendations.”)

But, healthy young adults, like the Queen, never died before “them bloody vaccines.” Surely it’s better to withhold the vaccines from them — just to be safe, right? Everyone’s heard they cause heart problems, and healthy young people are dying. No denying that.

So what’s the reasonable interpretation? Apparently the government removed the one-in-3.23 million clot risk vaccine, but won’t remove the vaccine that is destroying young people’s heart health and making them drop like flies?

Drugs That Work Have Side Effects. Period.

Antibiotics are powerful medicines with powerful effects. Any drug that has strong positive effects typically has some really negative effects too, for at least a few people: Antibiotics. Opiates. Chemo drugs. (Chemo is literally targeted poison.)

The cost-benefit ratio is what determines whether the drug is marketed. In the case of the J&J vaccine, one blood clot in 3.23 million doses was deemed an unacceptable risk, so the plug was pulled.

If a drug has no side effects (like homeopathy, for example) that’s a clue that it has no beneficial effects, either. A useful rule of thumb: “And it has no side effects!” means it’s useless, except perhaps as a placebo.

Any strong drug carries its dangers, but in previous generations, people trusted their doctors to make that call. If antibiotics were new in 2023, many people would reject them for bad reasons. That’s a problem.

Whose Job Is It to Know?

No one can be an expert in everything. My husband can fix almost anything, but he occasionally comes across an electrical, automotive, plumbing, or appliance problem that he can’t fix, and he calls in the expert.

Is the expert always right? Nope. Have we always been totally happy with the advice and outcomes we got? Nope. But overall, when it’s a problem we can’t fix ourselves, it’s best addressed by an expert. If you’re playing the odds, trying to optimize your outcomes, an electrician is the person to fix the mysteriously flickering light in the hallway.

Antibiotics, despite their strength and dangers, are an example of a very well-accepted drug. The doctor prescribes them, and patients usually go along with that, because they’ve been around and accepted since the 1940s — back when people trusted the experts.

I’d argue that we would do well to go along with reputable mainstream experts — and not our social media “research,” even if it looks like it comes from the CDC website or from a doctor with a lot of followers — on health questions.

Will the mainstream experts always be right? Nope. Will we always be totally happy with the advice and outcomes we get? Nope. But as a numbers game, we’ll probably be better off by listening to them. It also doesn’t hurt to look at what the doctors around us are actually doing. Do they give their kids antibiotics when they get sick? One of the best questions to ask a competent doctor you trust — especially if they’re giving you a decision to make — is, “If this were your child, what would you do?”

Obviously I’m Really Talking about Today

I wanted to frame this topic with something we’re all familiar with — antibiotics, which no doubt pose more dangers than covid vaccines — because it’s interesting to think about how readily many parents accept the risks of antibiotics, even as many of us avoid the smaller risks (and forego the benefits) of the covid vaccines.

Look, no one’s thrilled with the current vaccines. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a vaccine that was effective enough that 300 Americans weren’t still dying every day? Wouldn’t it be nice to have something effective enough that we’re not asked to get booster after booster? (Work just asked us to document our bivalent booster, which for some of us is our fifth covid shot.)

No one’s thrilled with the (dumb? clunky? misguided?) public messaging associated with the vaccines, either — as when Biden said that the unvaccinated would die en masse last winter, and the unthinkingly pro-vaccine “left” viewed the unthinkingly vaccine-hesitant “right” as bad, unhygienic, stupid, or “killing Grandma.”

Mixing politics with medical or public health messaging is a horrible idea, and I wish we could un-ring that bell, and trust that the information we were getting from leaders was the most accurate and neutral available. The trust issue — and how untrustworthy and politically driven our leaders have become — is at the root of a lot of our troubles and deserves its own post someday.

And yet again and again, there’s abundant evidence that we’re better off with the flawed, inadequate covid vaccines, despite the small risks associated with them, and despite the flawed, inadequate public messaging.

As Eric Topol wrote this fall, “Across all age groups age 18+ there is an 81% reduction of hospitalizations with 2 boosters with the most updated CDC data available, through the Omicron BA.5 wave.”

And what about kids?

In the three years from January 2020 through December 2022, 1600 kids in the United States have died of covid — and that was with schools shut down for much of that time.

Broken down to an annual number —533 a year — 500 kids is about as many who used to die annually of measles in the United States in the days before vaccines. That number was considered unacceptably high by 1960s parents. Now, 1600 dead kids in three years is considered basically “nothing” — a “cold” — “it doesn’t affect kids.”

There’s a level of denial that confuses me — on the one hand, the dangers of the vaccines are grossly exaggerated; on the other hand, the reality of dead children is glossed over.

We Have to Do Our Best for Now

Better treatments for covid are coming, no doubt. HIV infection was once a death sentence — for years, HIV-positive people expected to die of AIDS. Now excellent treatments have been developed so that people live long and happy lives with HIV.

If we wait a few more years, doing what we can in the meantime to keep covid under control with our imperfect tools, I’m confident we’ll have better ways to address covid as well.

Information can be both factually true and very misleading. We have to do our best to grapple with that reality and make good decisions.

These are fake Tweets, which I created for the sake of our thought experiment. The information in them is true. See BBC, ID Stewardship website, and CDC.

Very well done. You make a good argument for rational cost/benefit analysis.

Unfortunately no cost/benefit analysis was even allowed to be discussed throughout the lockdowns/remote learning/mandated vaccines/masking etc etc. Any risk was unacceptable then. Relative risks could not be examined, such as the huge risk differential between children and the elderly. I won’t question your figure of 1600 children dead in 3 years. How many of those were healthy prior to COVID, and how many had comorbidities?

It is true that people no longer trust experts as they once did. The experts brought that on themselves with their conduct during the pandemic, culminating in Dr Fauci claiming that anyone who disagreed with him was disputing The Science. Not sure of the number, but I believe it was thousands that signed the Great Barrington Declaration. Both Dr Fauci and Dr Collins moved quickly to squelch any reasonable discussion of it.

I liked the world better when we had confidence in experts to guide us. They destroyed that trust with their hubris. If experts want to understand the proliferation of vaccine mistrust, they should look in the mirror. They encouraged the very behavior you talk about- fear of any risk.

Great essay -- couldn’t fault any of the logic.

Out of curiosity, what do you think of Eric Feigl-Ding? And his recent “thermonuclear bad” tweet about China.

Also it’s well known capuchin monkeys are assholes