Yes, We Need to Keep Talking about the Lab Leak

Just like “Iraq has WMD” or “The Russians stole the election for Trump,” “SARS-2 arose naturally” doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

The day after Thanksgiving, I planned to finish reading Viral by Alina Chan and Matt Ridley and write a book review. Instead, I woke up and saw in my Twitter feed that we had a new variant to worry about: omicron.

And so, I got sidetracked, reading all I could about omicron, not really sure what aspects of this I would write about to prompt people to talk about the origin of SARS-CoV-2. But here’s the thing: understanding the origin of the pandemic, and applying pressure to world leaders to act accordingly, is the most important thing any of us could be doing.

The most important thing.

Hundreds of scientists have expressed concerns since at least 2014 that the type of research being conducted on viruses—so-called gain-of-function research, or GoF for short—could result in a disastrous pandemic.

But more on that in the second post. I’m breaking this into two parts so it’s not unbearably long for you: First, the original lab leak and a brief review of the book. Then, in the near future I’ll have a post about omicron, the ongoing concerns about GoF research, and what it all means for us.

Isn’t the Lab Leak a Crazy Conspiracy Theory?

Many people, without having heard the case for it or examining the facts, think the lab leak hypothesis is right up there with “Pedophile rings meet in the non-existent basements of pizza restaurants” or “Bill Gates planned the pandemic.”

That’s because, from the beginning, certain scientists promoted the narrative that considering a lab leak was a “conspiracy theory,” including Peter Daszak, who had a serious conflict of interest (he’s made his career on researching bat coronaviruses—so a lab leak would be a big problem for him). The letter in the Lancet in February 2020 simply stated that the virus came from nature—with no actual evidence, and a simple appeal to authority—and dismissed the other reasonable hypothesis (that it originated from a lab leak) with no basis for doing so: “We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin.”

But where’s the conspiracy? “This pandemic broke out in a city where research on these bat coronaviruses has been conducted for more than a decade. Moreover, none of the bats live within a thousand miles of Wuhan, no bats seem to have been at the market, and no evidence of the virus was found in any sources tested at the market. It makes sense to also check out whether it came from a lab.”

Where’s the conspiracy there in saying there are multiple hypotheses to be tested?

Nevertheless, the most vocal scientists seemed very eager to say a lab leak simply wasn’t possible. The Lancet letter was soon followed up by a second letter, “The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2” in March 2020 in Nature Medicine, which made the bold claim: “Our analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus.”

When you read the letter, though, you see “their analyses clearly show” no such thing. It is a remarkably content-free document.

I didn’t think too much of it at the time, except with some vague unease that “the experts” seemed very sure of the origin, very quickly, and didn’t present evidence to back up their claim or justify their certainty.

A Lesson in Parsimony

You might remember learning at some point that parsimonious explanations are considered a good thing in science. But in case you’ve forgotten: What are parsimonious explanations and why should you care? As this article explains,

“For every phenomenon in existence, it’s possible to generate an infinite number of incorrect explanations, the vast majority of which will be complex, convoluted, and highly specific to the situation at hand.

“Since these explanations, which are generally referred to as ad hoc hypotheses, are often difficult and costly to test, the principle of parsimony is a powerful tool that we can use in order to reject them in favor of more reasonable explanations for phenomena that we observe.”

That’s all very nice – but I tend to understand things better if I have some concrete real-world examples. So imagine you walk into your kitchen, and a toddler is sitting on the counter. There are cookie crumbs scattered on him and around him. There are chocolate marks on his face and hands. He’s sitting next to the empty cookie jar.

What happened to the cookies?

A parsimonious explanation might be: The toddler ate the cookies.

And there are an infinite number of less parsimonious explanations. For example, perhaps your house was burgled 10 years ago. It’s possible a burglar broke into the house again, undetected, didn’t trigger the Ring doorbell chime or appear on the security camera, went into the house, unnoticed by anyone, ate all the cookies quickly, put the toddler on the counter and sprinkled cookie crumbs and smeared chocolate on him, and then snuck out, again completely undetected.

It could have happened that way. I mean, the house has been burgled before, so maybe it happened again.

But which hypothesis is more parsimonious? “The toddler ate the cookies.”

Zoonosis Is Not a Parsimonious Explanation for What Happened in Wuhan in 2019

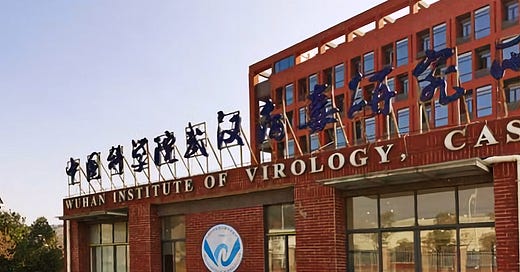

My unease at the lack of evidence presented for zoonosis (aka “it arose naturally in another animal and infected humans”), accompanied by an early insistence in the media that the cause must be a natural origin, only got more acute when I learned more details about the research conducted at the Wuhan Institute of Virology by Shi Zhengli and her colleagues.

Since at least 2007 the lab had been creating “chimeras” (simply put: the bat coronaviruses, plus some other altered bits and pieces), with the goal of making them more infectious to humans. This type of research, GoF research, is very controversial. (More on that in part 2.)

Why does anyone want to make viruses that are more infectious to humans? The official reason is that by studying these dangerous altered viruses, scientists can learn enough to prevent pandemics. Of course the obvious concern is that these viruses might get out and create a pandemic. (More on that in part 2, too.)

In any case, regardless of whether it’s a good idea, the scientists from the WIV had routinely been swabbing bats in southern China—a thousand miles from Wuhan—and bringing viruses back to their lab to do GoF experiments on them. Here for example is a $3.7 million NIH grant titled Understanding the Risk of Bat Coronavirus Emergence. Page 7 of this document lists Shi Zhengli as a co-investigator on this grant. (“The risk,” indeed.)

This is not pedophile-pizza-restaurant stuff on 4chan. This is documented, published, established fact in the Journal of Virology, NIH grant applications, and elsewhere.

Let’s think again about parsimony.

What is the simplest explanation by far for these facts? A bat-related coronavirus emerged in Wuhan, a city with labs that had been creating bat-related coronaviruses highly adapted to infect humans for many years. The virus was seemingly highly adapted to infect humans right away. No intermediate animal host has been discovered despite an exhaustive search.

The simplest explanation: “It leaked from the lab.”

That’s equivalent to the toddler and the cookie jar. Shi Zhengli and her colleagues are sitting on the kitchen counter, covered with crumbs and chocolate, and at the very least, that hypothesis that the lab is involved must be considered.

What is the less parsimonious explanation?

First, you’ve got to ignore Shi Zhengli, her colleagues, their proximity to the cookie jar, and the big pile of crumbs.

Instead, you suppose that the presence of the lab in Wuhan that had been creating these viruses since at least 2007 is completely coincidental.

Instead, you hypothesize that the virus is very similar to other bat coronaviruses, so it came directly from a bat.

Somehow the bat, who would typically be hibernating in a cave a thousand miles away, made it to Wuhan, a city of 11 million people.

Somehow the bat managed to infect the first people completely undetected. Its presence still hasn’t been detected two years later, despite extensive looking.

Or, the bat managed to infect an intermediate animal, perhaps a pangolin, which also is nowhere to be seen in the area, and then that pangolin was infected by the bat coronavirus, and its own pangolin coronavirus, and then those two viruses combined in that pangolin, along with a third virus which happened to have a furin cleavage site, and then that created a super-infectious-to-humans virus through a completely unlikely and unknown mechanism, and then that pangolin or other animal managed to infect people if it wasn’t directly from the bat—but that, too, was completely undetected, and that animal hasn’t been detected either.

You’ve got to ignore the fact that in earlier pandemics, the animal origin was easily identified.

Somehow the virus, even though it evolved naturally in a non-human animal, was oddly adapted to infect humans—again, quite unlike the pattern of other zoonotic outbreaks, where the virus is not adapted to people, but adapts itself to people after it makes a zoonotic leap, through many intermediate phases.

Whether or not it popped up from a phantom bat or phantom pangolin, we’ve still got to account for the fact that somehow this naturally arising virus had a furin cleavage site. No furin cleavage sites had ever been seen in the thousands of samples of these viruses collected from bats, and the fact that Peter Daszak via the EcoHealth Alliance had reportedly submitted a proposal to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in 2018 to partner with the Wuhan Institute of Virology in modifying bat coronaviruses by inserting furin cleavage sites into them is just another crazy coincidence.

The fact that the raison d’être of Shi Zhengli’s research—established, documented, published in respectable journals and grant proposals—was to create and study bat coronaviruses adapted to infect humans is another crazy coincidence.

We might expect that the researchers or the Chinese government would be motivated to clear up any doubt about all these crazy coincidences. Instead, they deleted databases and refused access to their lab. But in this hypothesis, that behavior is completely unrelated. Ignore all that.

This version of events is “Never mind the crumb- and chocolate-covered toddler in the house. A burglar did it, completely undetected.”

“Parsimony” Does Not Equal “True”

Just because an explanation is parsimonious doesn’t mean it’s true. (Maybe the toddler happened to climb up there and crawled in the incriminating crumbs left by others.)

But when you start with parsimonious explanations, you are much more likely to start from a place approximating the truth, which can lead you in a helpful direction. To solve your cookie mystery, you’d do well to start by looking at the people who were home at the time. Looking for a burglar is probably not going to solve your cookie mystery. We need to start with all the facts and then apply critical thinking and common sense to them.

So Now for the Book Review – Sort Of

I’d been following this story for about two years, and I read Viral thinking I would not learn much new. I was wrong. The facts surrounding this mystery are laid out in such thorough and interesting detail that I encourage you to read the book even if (1) you think you already know all about it; or (2) you fear it would be boring, either because you’re not a scientist (furin cleavage blah blah receptor binding domain blah blah epitopes) or because you are (and you envision getting annoyed with dumbed down explanations). It’s neither overly detailed nor dumbed down.

It’s informative. It’s well-researched and well-written. It’s not boring. Read it. The competing hypotheses come into much clearer view, something which I thought (for me) would not be possible, although my one quibble with the book is that toward the end, it presented each hypothesis in turn as “Hey, it could’a happened” when in fact they seem about as balanced as the toddler-vs.-burglar cookie-eating hypotheses are.

Perhaps this was a requirement of publication—to “be fair” or to “present both sides”—because it’s hard to believe that’s what either author really thinks. Perhaps it was just a natural extension of Alina Chan’s “We just don’t know for sure” stance on Twitter. I admire her and can’t begrudge her natural impulse to protect her own (still early) career. She risked a lot and used her own name to do it.

But at some point when it comes to SARS-CoV-2, “We just don’t know for sure” sounds an awful lot like “Maybe the toddler, maybe a burglar, we just don’t know for sure who ate the cookies.”

There’s a lot that happens in the world that we don’t know for sure. We may never know exactly what happened with SARS-CoV-2.

What do you think about the lab leak hypothesis? And do you think it matters?

I believe that the virus did leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology. And yes, it very much matters. The pandemic has shown a disturbing lack of critical thinking and just plain common sense in our populace.

People were frightened, and more than willing to cede all authority to the scientists who were going to save us. And the wet market theory was easily sold; it conformed to what has happened in previous viral outbreaks, and wet markets are disgusting to American sensibilities. It wasn't difficult for Dr Fauci and his colleagues to convince people that it was purely coincidental that the lab was located in the epicenter. I think it was understandable that people bought this at first.

But as it became clear that there was no evidence to support the wet market origin, institutions dictated that only the pronouncements of their preferred "experts" mattered. Other evidence and contrary expert opinion were deemed "dangerous". As you so eloquently point out, common sense dictated that the obvious should have been investigated.

Have people simply abandoned evidence, logic, and common sense in favor of perceived "safety"? I think many have done exactly that, if they ever had any critical thinking skills to begin with. But I also think many more fear the power of the authoritarian social media if they dare to step out of line and think for themselves.

The pandemic has been horrific. What it has revealed about authoritarianism in our institutions and media is even more frightening. And most frightening of all, it has shown that people will not only accept it, but actively promote the idea that questioning official pronouncements is "dangerous misinformation".

So yes, in my opinion it matters very much.

I haven’t read much on the origins debate; it didn’t matter much to me at first. Not that it *doesn’t* matter, just that I didn’t have the personal bandwidth to pay attention. So I never really knew why lab leak was considered a conspiracy theory (though I knew it had been called one). Sounds like a lot of ass-covering behavior going on. Thanks for this post.