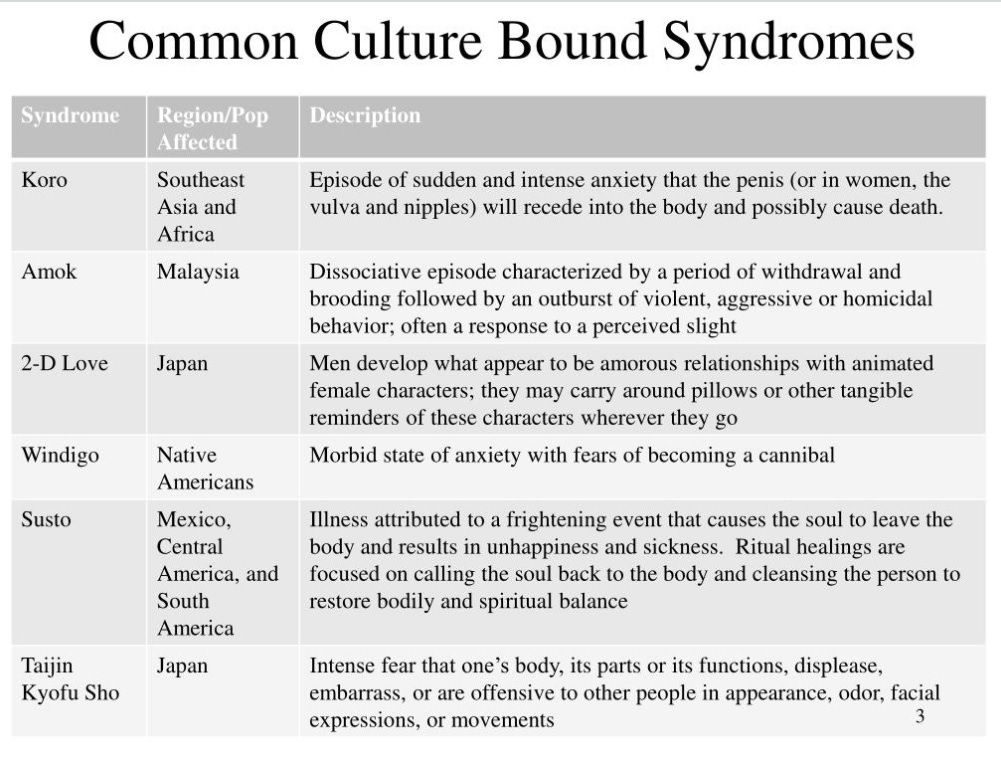

Whether from a college class or clickbait, many of us have heard of unusual psychiatric ailments that people in other cultures experience: Some people in Malaysia “run amok”; some people in Africa experience “koro”—the fear or belief that their penis will shrink into their body.

Even when accompanied by calls for greater cultural sensitivity, the unfortunate takeaway is still usually that our superior Western understanding of anxiety or trauma or anger management is the scientific and true understanding, and those other cultures with their funny beliefs are backward compared to us.

If you’re not already familiar with them, here are a few culture-bound syndromes to give you the general idea:

Take windigo, for example. The modern Western take seems to be something like this: Windigo and the extreme anxiety associated with it are real. Humans are wired to experience anxiety, and human behavioral traits exist on a spectrum. Therefore, a few unfortunate outliers in every culture, in every time and place, will experience extreme anxiety. The cannibalism thing, though, is something that a particular culture layered on top. It’s very real to the sufferers, but it’s also true that a culture “made it up.” Other cultures tell the story about their anxiety in different ways. They express and experience their anxiety in other ways. The cannibalism thing represents one culture telling a story about anxiety. In other words:

Anxiety is a human universal. Windigo is something they made up.

That’s not to say that people who experience windigo aren’t suffering with something real—they are. Their experience is real. They’re not pretending. It feels natural and organic. In their context, it makes sense.

But how does that happen? How do cultures hit upon the specific stories they tell about the nature of a universal human experience? It’s not clear. But Ronald Simons, a psychiatrist who’s studied culture-bound syndromes, has described it this way:

“Unlike objects, people are conscious of the way they are classified, and they alter their behavior and self-conceptions in response to their classification.”

It’s really easy to point this out when it happens in other cultures. Only if you live in a culture where the extreme anxiety related to becoming a cannibal is “a thing” is it possible for your own wired-in extreme anxiety to find a home in that fear.

It’s harder to point this out in our own culture, though. Only if you live in a culture where cutting yourself to express your emotional pain is “a thing” is it possible for your own emotional pain to find a home in cutting yourself. That seems less intuitive because it’s the water in which we swim. (Isn’t that “just what people do”? No, it’s not.) Nevertheless, our own culture is full of culturally created beliefs, too.

Trauma, Shell Shock, and PTSD

Whether or not they’ve given the matter any thought, most 21st century Western people probably share the belief that PTSD is a predictable human response to trauma. It’s widely viewed as a human universal. Trauma reactions have been documented for thousands of years.

Well, yes and no. PTSD is a bit like windigo. There’s a universal human experience at the core, and there’s a bunch of cultural stuff laid on top.

Let’s look at Western symptoms in response to trauma at a few different time points:

In about 440 BC Herodotus, in writing about the battle of Marathon, described a soldier with symptoms in response to emotional trauma that developed during a sword fight: he suffered psychogenic blindness and frightening visions of a giant enemy soldier.

Flash forward a couple thousand years: In World War I, “shell shock” was described as a trauma response to war: “The main causes are the fright and anxiety brought about by the explosion of enemy shells and mines, and seeing maimed or dead comrades ...The resulting symptoms are states of sudden muteness, deafness ... general tremor, inability to stand or walk, episodes of loss of consciousness, and convulsions.”

Then, just a few decades later, in the post‒Vietnam War era, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was officially recognized in the DSM-III, the diagnostic manual used by psychologists and psychiatrists. The full criteria are somewhat lengthy, but basically, instead of being shut down like the World War I vets, the new PTSD diagnosis required symptoms of hyperarousal, including

“difficulty falling or staying asleep…irritability or outbursts of anger…difficulty concentrating…hyper vigilance…exaggerated startle response…[and] physiological activity upon exposure to events that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event.”

In the new conception of PTSD, there was also an aspect of “reliving” the old trauma in response to triggering events.

The stereotype of the World War I vet was of someone who was so shut down he withdrew, and his physical symptoms corresponded to that. The stereotype of the Vietnam War vet was of someone who was so high strung he would dive for cover when he heard a weather helicopter and become combative and confused.

And now today, in the early 21st century, compared to the past 2,500 years in which trauma responses were widely acknowledged to occur in response to an “event that is outside the range of usual human experience” such as war, the definition of PTSD has expanded to include responses to all sorts of lesser events.

As the Mayo Clinic website describes it, “Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition that's triggered by a terrifying event — either experiencing it or witnessing it. Symptoms may include flashbacks, nightmares and severe anxiety, as well as uncontrollable thoughts about the event.”

No longer just survivors of extreme events “outside the range of usual human experience” but people who’ve suffered more common human experiences, like bullying, are now conceived of as being vulnerable to PTSD as well.

Again: “people are conscious of the way they are classified, and they alter their behavior and self-conceptions in response to their classification.”

This might explain, for example, why there was no such thing as being “triggered” by emotionally difficult lecture material in 1975, and yet we’ve heard about it often in recent years. Our current cultural understanding is that it’s possible to have a trauma response to upsetting educational content—it’s now become a thing for us, just as the fear of becoming a cannibal is a thing in another culture—and so if a lecture is upsetting, it can (really) result in being triggered now.

No one is pretending. Our cultural expectations shape our reality. Both those things can be true.

There’s always a human universal underlying these phenomena. The human universal here is that humans sometimes have extreme responses to traumatizing events. But the specific ways they respond, and even what they consider to be trauma, change depending on time, place, culture, and context. Trauma responses are very real. But culture lays a lot of things on top of it. Culture tells you how to respond, but you’re not aware that’s happening, so the response feels like it’s coming from inside you.

The Power of Culture

Cultural definitions, cultural beliefs, and cultural expectations are really powerful. They influence people’s beliefs and behaviors in ways of which we ourselves are often unaware. Culture essentially tells us how to behave, and we comply without perceiving that we’re complying. The World War I vet with shell shock feels his experience arose naturally. So does the Vietnam vet with PTSD, or the 21st century college student who’s triggered by a lecture. None of these people’s experiences would exist the same way in a different time or place.

Culture-bound syndromes are not just for quaint, unaware people in other places. They are very much alive. Cultural beliefs exert powerful effects.

Note that no one is play-acting—no one is pretending. But people in our culture—not just other cultures—adopt sets of beliefs and behaviors without being aware of it, in response to cultural expectations, in ways that feel completely organic and genuine.

If you want to read a book on this topic with a lot of detailed and well-researched examples, check out Crazy Like Us. Anyone who’s been alive long enough, however, can think of their own examples. A lot of people can remember when anorexia and bulimia just weren’t a thing—nor was cutting—but now those are entrenched Western conditions which have spread to other places in the world, each with their own mythologies of meaning. To the sufferers they feel genuine. They are genuine. But they are also culturally created. They are made up.

So when we look at human suffering and how to address it, it can be helpful to ask ourselves: What part of this thing is a human universal? Which parts did we make up?

Trans as Cultural Phenomenon

To hear the modern Western media tell it, transgender identity and gender dysphoria (extreme emotional distress related to aspects of your sexed body) have always existed among humans. The most common comparison made is to same-sex attraction (and yes, same-sex attraction is a human universal: same-sex attraction has existed throughout time, place, and culture).

If our current cultural narrative is correct—if trans identity is a human universal the same way that same-sex attraction is—then it follows that a compassionate society must accept it, validate it, and—ironically, since we’re also told it’s healthy and normal —treat it medically in very expensive, health-compromising, and permanent ways.

People who claim that trans identities are universal often mention in support of this claim that trans people have always been around. They point to two-spirit people in certain indigenous American cultures, or the fa’afafine in Samoa.

Not only is trans identity a human universal, the current narrative goes, but our current 21st-century response to it is the universally decent way—the only right way—to respond to someone with such an identity.

Thus, the 21st-century Western narrative calls for affirmation of everyone with a trans identity, changing the names and pronouns we use for people, providing puberty blockers and hormones, offering surgeries, changing single-sex spaces and sports to single-gender spaces and sports, and endorsing simple catechistic slogans with which every decent person is supposed to agree (e.g., “Trans women are women”). The reality is so settled that there is to be “no debate.”

But the existence of two-spirit people and fa’afafine is evidence for something very different: There is something universal underlying the phenomenon of all these variations of gender expression and gender identity, but the fact that gender expression around the world is so diverse reveals that the identities themselves are culturally created. The specific and highly varied cultural manifestations of gender identity are not universals. That means we need to take a closer look to figure out what’s really universal and what’s not.

Gender Nonconformity Is Universal

If likes, dislikes, interests, and personality traits vary among individuals, it’s necessarily true that a few people will be extreme outliers with regard to any behavioral traits. For example, suppose you’re born into a culture where women are expected to stay home with the babies and men are expected to be warriors. We know, just due to normal human variation, that some women will very much want to be warriors and some men will very much want to raise babies, and those outliers are going to be somewhat at odds with what society expects of them.

Depending on whether people find their nonconformity supported or punished by their culture, the outcomes could be adaptive or not, happy or not.

When you see gender nonconformity expressed in two-spirit cultures, Samoan fa’afafine people, or 21st century American trans people, the common thread is not the idiosyncratic ways in which each group expresses itself and holds beliefs about itself, but rather their universal underlying gender nonconformity.

So when we’re told “Trans identities are universal; they’ve always existed,” we need to understand that’s not quite true. Trans identities as they exist in the 21st century West, with their specific baggage and cultural beliefs, are not human universals. Gender nonconformity is what you find in every time and place. That’s the human universal.

Where’s the Dysphoria?

Imagine a two-year-old boy who likes long hair, sparkly dresses, and dolls. If everyone around him conveys the message, “You’re great how you are! Have fun growing your hair and playing with dolls. You’re a cool kid,” then where would our modern Western notion of “gender dysphoria,” which needs “treatment,” ever creep in?

Imagine everyone around this child supports him: he can play with the other kids who like dolls and be accepted, he is accepted by his family and community, he’s never bullied or mocked, no one at school or in the media ever suggests that his personality and likes or dislikes might mean he’s “really a girl.” And indeed, what could that possibly mean, to “really be a girl,” given that his body just is how it is? His sex characteristics, just like his height or eye color, are unrelated to his personality.

How would this child ever come to believe that his body, his pronouns, or his name are displeasing, if there’s no wrong way to be a boy? How would he come to feel that any of those things need to be changed on the basis of his toys, hobbies, and clothing preferences?

Some people in the 21st century West will answer, “I don’t know. But it just happens. There’s some kind of mismatch between brain and body.”

OK. Gender dysphoria does happen in the 21st century West. Windigo happens, too, in its cultural context. It’s all real. Let’s leave aside for a moment the fact that there is no medical evidence for any kind of brain-body “mismatch,” or even a reasonable hypothesis for how such a mismatch could possibly manifest or be tested.

If this brain-body mismatch were to exist, we should find it —like same-sex attraction—appearing in every time, place, and culture, not just ours. Gender dysphoria should exist across every time and place.

But indeed, you don’t find gender dysphoria everywhere—and therefore you don’t find support for the notion that this form of emotional distress must be treated medically, because that form of emotional distress doesn’t exist in places where gender nonconformity doesn’t need to be corrected at all. Again, let’s look at the fa’afafine.

Traditionally the fa’afafine perceived themselves as feminine men, who dress as women and participate in “feminine” activities like housekeeping. It’s a niche they occupy, with no cultural history of believing themselves to be in the wrong body, of being deeply unhappy and distressed, of needing to change their body, of familial rejection, or of needing other people to behave as if they believe they are “really women.”

In fact, the word fa’afafine means “in the manner of a woman”—there is no concept of transwomen (and no notion that “trans women are women”) in that culture. That being said, Western ideas have been spreading, as seen for example in this story about a Samoan fa’afafine soccer player talking about other fa’afafine adopting estrogen and breast implants.

Even then, though, there is no mention of distress or “dysphoria” as the reason. Some fa’afafine now take estrogen because they find it aesthetically pleasing, just as some Victorian women once took Dr. Rose’s Arsenic Wafers for a nice complexion.

Gender dysphoria and gender medicine, we need to understand, are recent Western notions, not human universals. Our doctors diagnose gender dysphoria as if it were something like a broken bone—you have X condition, so you need Y treatment. But gender dysphoria is more like windigo than it is like a broken bone: all cultures have people with broken bones, but not all cultures experience gender dysphoria, and not all cultures have our notion of “being trans.”

Trans Is Something We Made Up

To the extent that other cultures throughout history have not partaken in the belief that you can be “in the wrong body”; to the extent that those cultures’ gender-nonconforming people have not experienced extreme bodily distress, accompanied by a strong desire to change their bodies; to the extent other cultures’ gender-nonconforming people don’t believe they are literally the opposite sex and expect others to believe it; and to the extent that other cultures don’t have a “transition or die” suicide narrative; trans is something that we created in our own culture as a response to gender nonconformity. Trans is something we made up.

Like any cultural creation, it deserves close scrutiny: Is it helping or hurting?

If you look at the Samoan response, where the fa’afafine are integrated in society, expressing themselves in ways they enjoy without the need for medical or psychiatric treatment, without the constant specter of suicide and misery dictating how the rest of society perceives and treats them, you could be forgiven for believing that Samoa created a better cultural response than the 21st century West, with its typical consumer-based, problem-and-solution narratives.

Just as deodorant sales are much better if advertisers convince you that you stink, gender medicine is a much better business if people believe their bodies are all wrong because they don’t match their personalities -- and if they believe they won’t ever be happy unless they buy a solution.

But money and consumerism aside, look at the two cultural narratives. The Samoan fa’afafine have a defined cultural role and seem to thrive in it, without all the trappings of Western trans medicine. The Western trans people, on the other hand, are defined by a narrative of wrongness that needs to be fixed—and poor mental health.

It's Time to Reassess

If gender nonconformity is the human universal and being trans is the cultural baggage, it’s time to reassess a cultural approach that is based on human misery, suicidality, and expensive, irreversible medical treatments.

In absence of medical evidence that anything is wrong with any gender-nonconforming person’s body or behavior, let’s reassess our cultural view that it’s appropriate to treat trans people medically. Instead of raising kids in a culture that’s so hostile to gender nonconformity that they think transition is the key to being happy and fulfilled, let’s work on building a culture where we deeply believe that gender-nonconforming people are as awesome as anyone else and can express themselves freely.

Just as there are no tall people trapped in short bodies, no Asian people trapped in white bodies, no hazel-eyed people trapped in blue-eyed bodies, there are no people trapped in wrong-sex bodies. That’s something we made up. Our bodies, our personalities, our hobbies, our ways of adorning ourselves just are what they are.

Trans is something we made up. We can make up something much better.

I read this essay when it first landed in my inbox but I was eyebrows-deep in work at the time. I just want to say thanks for writing it. As a scholar with expertise in the social history of medicine, women, and gender, I agree with every word.

I'm at a loss how to stem the tide among my young-adult students. I do pose questions about the dogma, and I'm intent on doing so in a way that conveys my love for my many gender non-conforming students. But by the time students land in my classroom, they're thoroughly marinated in ideas about gender that kids propagate to other kids on Tumblr, Insta infographics, and now TikTok. Many of the trans-identifying young people have already medicalized.

Even the brightest of my students will parrot things like "trans women have periods" and "there are six sexes." The latter statement came from one of my own kids; we had a talk about what that Y chromosome does, or more precisely the SRY gene, in people with atypical configurations of X and Y. But my kid knows I've been standing up for gender-atypical people since before he was born. Questioning the current dogma in the classroom risks my livelihood, yet I'm doing it as much as I can without so alienating students that they tune me out or get me fired.

I've been caught in a crisis of conscience for five years now and I feel powerless to stop the onrushing train. Twenty years ago, hardly any feminist scholar envisioned that contesting the rigidity of binary gender norms would result in the mass medicalization of children. Why have so many of us gone along with it? Certainly a big piece of the explanation is careerism for those whose research is congenial to the dogma. Possibly an even bigger piece is that anyone who raises questions would immediately branded a transphobe or TERF, pilloried in public, ostracized, and quite likely fired or hounded out of their positions. It's hard to know what proportion of feminist scholars fall into each camp because almost everyone in the latter group is terrified.

If I thought speaking very bluntly in public would save a single young person from unnecessary medicalization, it would be worth getting fired. But instead, I'd be branded a TERF and my arguments immediately dismissed. It's an awful Catch-22. I have been speaking privately with some local mothers whose tween girls have identified as trans, and once publicly on FB with another local mother whose daughter was about to have top surgery. The latter conversation didn't make any difference. But conversations with mothers of younger kids have been helpful to them, I think.

My apologies for barging into an old thread. I just wanted to let you know that I deeply value this essay - as a scholar, mother, and human. Please keep writing about this topic. I'll keep pushing the envelope as best I can in my sphere. It's not nearly enough. It's also not nothing.

As an ex trans 'woman' I can attest to everything you describe here.

There is no gene that encodes for long hair, dresses, and pronouns, and it's absurd to live life believing that.

I medically and socially transitioned from male to female and lived that way for 4 years.

I'm grateful to have found truth, and found a way out of those destructive thought patterns.